Full-Tilt Retribution: "The Card Counter" Review

★★★ (3/5)

If we can deduce anything from the life of a career gambler, it’s the fact that it isn’t accurately depicted in popular movies like Ocean’s Eleven or The Hustler; as two-time WSOP champion Doyle Brunson once said, “poker is a hard way to make an easy living”. In order to succeed, gamblers must entrench themselves in a lifestyle that is both grating and solitary. To repeatedly throw oneself into a series of psychological confrontations is a way of life that requires discipline, one that does not boast with glamor but rather unspoken virtue.

Ironically, The Card Counter isn’t actually about gambling. Much like Paul Schrader’s acclaimed 2018 spiritual drama First Reformed, his latest is a fitting (albeit sometimes formulaic) counterpart as an unflinching character study about a man grappling with the consequences of guilt. Schrader’s protagonists generally live a reclusive existence, with time and means to examine the existential nature of their vulnerabilities, all enslaved to their sins in one way or another.

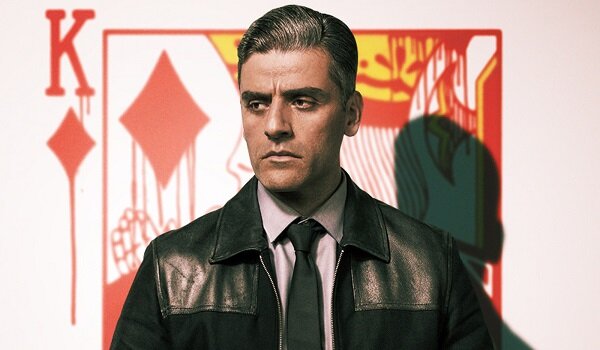

Driven by a career-defining performance from Oscar Isaac, The Card Counter follows a discharged military vet who makes his living as a traveling gambler in an effort to drown out the noise of his violent past at Abu Ghraib. Isaac’s portrayal of the film’s morally splintered protagonist William Tell is a tour-de-force that demands your attention for every second that he’s onscreen.

Throughout the film, Tell wears a permanent ice-cold gaze that’s steadied by an unwavering constitution, a regimented discipline that establishes character with meticulous depth. As the details of his life begin to unravel, we come to learn that his code is his penance, a forced veneer. When a shadow from his enigmatic past comes crashing into his present, it threatens the brittle fabric of Tell’s minimal existence.

Not since 2014’s A Most Violent Year has Oscar Isaac been more effectively utilized in a nuanced, dramatic role. Between this, the forthcoming Dune, and HBO’s new adaptation of Scenes from a Marriage, he’s making a strong statement for why he should be recognized come awards season next year. His portrayal of William Tell invokes an unshakeable fortitude but behind his cold, dead eyes lingers a horror that is far beyond comprehension.

Having written such enduring Scorsese classics like Taxi Driver and Raging Bull, Paul Schrader has cemented his long, noteworthy career with gripping stories that navigate similar themes. From an alcoholic depressive priest in First Reformed to an ambivalent middle-aged drug dealer in Light Sleeper, his films often follow degenerate men who are tormented by their own frailty. Their arc is essentially a path of self-destruction to find enlightenment in moral reckoning.

In true Schrader fashion, The Card Counter re-purposes the classic motif of a protagonist sitting alone in the dark, scribbling thoughts on a notepad with a glass of whiskey close at hand. Having been raised a devout Calvinist, Schrader’s inherent religiosity manifests itself in this cathartic, almost confessional aspect in many of his films. This grounding in spiritual realism provides sincere perspective about the nature of self-reflection and internal conflict.

William Tell is one of Schrader’s most complicated creations; he’s a man of intense focus and sage wisdom, but an undercurrent of violent instability like Taxi Driver’s Travis Bickle. His somber assertation that “any man can tilt” is a distillation of the film’s larger commentary—a genetically implanted idea that anyone in the right set of circumstances can reach their breaking point. Much like the films of Sam Peckinpah, one of Schrader’s most influential directors, his art seeks to explore the depths of man when pushed to the brink of his limits.

All said and done, The Card Counter isn’t without some glaring weaknesses in the way it follows too closely in the footsteps of Schrader’s previous work. While the film certainly goes in some unexpected directions, its dramatic beats are nearly identical to many films that have already been explored in the Paul Schrader canon. As viewers, we implicitly get that his movies explore themes of regret and reflection, but you can’t help feeling that by this point, he’s retreading old ground with new people.

What ultimately sets this film apart is the acting and the depths they bring to its characters. Alongside our protagonist, we find La Linda (Tiffany Haddish), a gambling backer who brings a certain degree of warmth and understanding to William’s life that he doesn’t quite feel he deserves. Between them stands Cirk (Tye Sheridan), a wild card who unexpectedly enters William’s life with a dangerous proposition that crashes the status quo of his equilibrious lifestyle.

Tell finds himself torn between the two polarities that La Linda and Cirk can both provide: one being the hope for self-acceptance, the other being a swirling descent back into a life of corruption. The fate of our soul must be chosen with care and autonomy; this compelling conflict is the cornerstone of all of Paul Schrader’s work, a cinematic artist who strives to show that there’s always beauty in the breakdown.